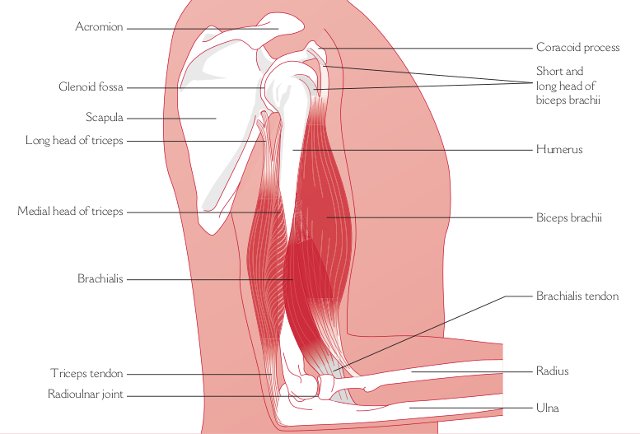

The arm-bone (humerus) is the single bone forming the upper arm. It is part of the shoulder joint at its upper end, and the elbow joint at its lower end. Its top is rounded on the inner side, forming the head of the bone. This part is the ball which matches the socket of the glenoid cavity on the shoulder-blade to form the shoulder (glenohumeral) joint. At the outer side of the top of the arm-bone is a knob called the greater tubercle (or tuberosity), which you can feel if you press your fingers just below the acromion at the top of the shoulder.

Immediately below the rounded head of the arm-bone is a line called the anatomical neck, around which the capsule of the shoulder joint is attached. The demarcation point where the top of the bone joins the narrower shaft is known as the surgical neck.

The shaft or long part of the arm-bone is roughly straight, and the bone widens out at its lower end to form a central knuckle called the trochlea, and a rounded part to the outer side of the trochlea called the capitulum. The trochlea links to the top of the inner forearm-bone (ulna) at the elbow, forming the humeroulnar part of the elbow joint. The capitulum is joined to the head of the outer forearm-bone (radius), forming the elbow’s humeroradial part.

The lower end of the arm-bone spreads out sideways each way, but more on the inner side than the outer. This is why the forearm doesn’t hang vertically, but is set at an angle away from the body. This angle is called the “carrying angle”, and is greater in females than males.

There are two small protrusions called epicondyles on either side of the lower end of the arm-bone. The protrusion on the inner side of the bone (leading down to the little finger) is called the medial epicondyle, while the lateral epicondyle is on the other, outer side (which leads down to the thumb). You can feel the medial epicondyle easily by pressing it with your fingers, just above the inner side of the elbow, with your arm by your side and palm facing forwards. The medial epicondyle is also known as the “funny bone”, because the nerve which lies directly behind it causes odd sensations if the bone gets knocked. The lateral epicondyle can also be felt with your fingers, especially from behind, just above the outer side of the elbow. The front is harder to feel, because the muscles covering it are quite thick.

The epicondyles are the attachment points for the tendons of muscle groups which control the forearm and hand. The common flexor origin is attached to the medial epicondyle: the flexor muscles bend the wrist and fingers against gravity or a resistance. The common extensor origin is attached to the lateral epicondyle, and the extensor muscles act to extend (straighten) the wrist and fingers against gravity or a resistance, and they play a vital part in stabilizing the wrist to give the hand a strong grip. Problems of injury or inflammation affecting the common extensor origin and lateral epicondyle are known as “tennis elbow”, while in the common flexor origin and medial epicondyle they are called “golfer’s elbow”.

At the lower end of the arm-bone, which is the upper part of the elbow joint, there is a knuckle, called the trochlea, which forms the upper part of the joint with the inner forearm-bone (ulna). To the outer side of the trochlea is a rounded surface called the capitulum, which is the receiving surface for the top of the outer forearm-bone, (radius). Just above the back of the trochlea is a quite deep hollow, called the olecranon fossa, which receives the very tip of the ulna (called the olecranon process) when the elbow is fully straight. On the front of the arm-bone, just above the trochlea, there is a similar but smaller depression called the coronoid fossa, which receives the tip at the front edge of the ulna, called the coronoid process, when the elbow is fully bent.

The main muscles of the upper arm are the biceps and triceps, which are two-joint muscles acting on both the shoulder and the elbow, and brachialis, which acts on the elbow joint.

The biceps brachii has two heads, the long head starting as a tendon from a notch just above the glenoid cavity on the shoulder blade, which forms part of the shoulder joint, while the tendon of the short head is attached to the top of the coracoid process, a little bone jutting forward from the upper part of the shoulder blade. The two parts join up to form the biceps muscle, which is the main bulky muscle on the front of the upper arm - the one that muscular sports players like to flex when they’re “pumped up”. At its lower end, the muscle forms a tendon which is attached below the elbow, mainly to the back part of a knob (radial tuberosity) on the outer forearm-bone (radius), although there is a part which fans out to spread inwards and join the upper part of the forearm flexor muscles. The biceps tendon stands out when you bend the elbow and turn the forearm outwards, palm facing up, into supination.

Bending (flexing) the elbow and turning the forearm outwards into supination are the main actions of the biceps muscle, when it works concentrically against gravity or a resistance. Working eccentrically, it controls the reverse movements of straightening (extending) the elbow and turning the forearm inwards into pronation, under the influence of gravity or a load. When you lift a cup to your mouth or do chin-ups to a bar, your biceps muscles work concentrically and eccentrically.

Biceps also helps to bring the arm forward at the shoulder, working concentrically against gravity or a resistance, while the long head helps to keep the top of the arm-bone steady when the deltoid acts to lift the arm sideways.

The nerve which controls the actions of biceps is the musculocutaneous nerve, from the 5th and 6th cervical levels of the spine. Each part of the muscle has its own nerve branch.

The triceps is the fleshy muscle on the back of the upper arm. It is a three-headed muscle. The long head starts as a tendon attached to a knob (tubercle) just under the glenoid cavity on the shoulder blade. The lateral (outer) head is fixed by a tendon to the back of the shaft of the arm-bone (humerus), and is also attached to the band of tissue which separates the muscle compartments (technically called the lateral intermuscular septum). The medial head covers most of the back of the arm-bone. The three heads come together to form a tendon at the lower end of the muscle which fixes mainly on to the top of the ulna, on the part called the olecranon.

Triceps straightens (extends) the elbow when it acts concentrically against gravity or a resistance, bringing the forearm into line with the upper arm. It controls the opposite movements, when it acts eccentrically under the influence of gravity or a load. The press-up exercise is an example of concentric and eccentric triceps action.

The nerve controlling triceps action is the radial nerve (C6,7,8), and each head is supplied by a separate nerve branch.

Brachialis lies under the biceps muscle, and its upper part is attached to the front of the arm-bone. At its lower end, it forms a tendon which fixes to the upper part of the shaft of the inner forearm-bone (ulna). Working concentrically against gravity or a resistance, brachialis acts to bend (flex) the elbow, bringing your hand up towards your shoulder or head. It works eccentrically to control the reverse movement under the influence of gravity or a load.

The musculocutaneous nerve (C5,6) controls brachialis activity.

© Vivian Grisogono 2008. Updated 2014, 2016